The Paris Dakar: The most gruelling race on Earth

Sometimes getting lost is a good thing. It was for Thierry Sabine. The French Motorcycle rider was taking part in the Abidjan-Nice rally in 1977, when he got lost. In a desert.

*All images courtesy dakar.com

Most of us would likely feel a bit of panic set in. Probably just sit there and watch the camels walk past for a while, wondering how long we’d last without water. And really craving one of those ice creams with hundreds and thousands on the end.

Theirry was built a little differently though. All he could think of was how nice the desert was and wouldn’t it be great to race across it. So when he returned to Paris, he set about organising a new race.

Paris-Dakar: “A Challenge for those who go, a dream for those who stay behind”

It didn’t take long for Theirry to get things sorted and rustle up some interest in his new race idea. On December 28th 1978, engines were started for the first time and 182 competitors were about to find out just how difficult this thing named the Paris-Dakar was. Over the days that followed, more than 100 of them would succumb to the course, failing to make it to the finish line.

Cyril Neveu, riding his Yamaha 500 XT, was first to the Place de L'Independance in Dakar. It was the end of a 10,000km ride through France, Algeria, Niger, Mali, the Upper Volta and Senegal... and the beginning of a racing legend and a legendary race.

Part of the appeal was in the stark contrast of the landscape, which made for compelling viewing. The bikes, cars and other vehicles would be observing the road rules in a major city during one stage. The next, they’d be going as fast as possible and racing past mud huts as villagers looked on a little bemusedly.

By year 2, word was already spreading and the entrants rose to 216, of which 81 made it to the chequered flag. Yet the race still remained relatively unknown and was very much an amateur competition. Then the son of the so-called Iron Lady went missing.

Mark Thatcher was reportedly completely unprepared for the rally. His choice of a long wheelbase Peugeot didn’t help matters. It didn’t like the bumps too much so when the rear axle broke between Tamanrasset and Timeiaouine in Algeria, it probably wasn’t too much of a surprise. That all of the passing other racers failed to accurately note his location probably would be a little surprising though. So he spent 6 days in the desert with his crew, whilst Mother Dearest (who happened to be the Prime Minister of Great Britain) was likely a little concerned. She was certainly concerned enough to fund the Algerian Military to try and find him. They did, which was good, because as he said at the time, he needed a ‘beer and a sandwich’.

In the next few years, more and more professional teams got involved and everything moved up a notch or two. Including the danger levels. Then came the 1986 rally, later to be known as ‘The Black Year’. From the start, there was a sense of foreboding about it. A Japanese motorcycle rider was hit by a car and died. Retirements mounted up quickly as the weather closed in. A Hercules plane was commandeered for use as an emergency hospital of sorts. A press plane crashed. A French racer was brought unconscious from the desert to a makeshift operating area by an airstrip, where he was operated on. Jean Michel Baron then slipped into a coma from which he never awoke. He died in 2010.

Then it got worse. Thierry Sabine was not only the founder of the rally but also the heroic rescuer of many competitors, his helicopter racing to find the injured and crashed. Until it didn’t. A sandstorm bringing down the Eurocopter AS350 and killing everyone on board, including famous French singer, Daniel Balavoine.

The race went on, that year and in the years that followed. Nowadays, it’s known simply as the Dakar. It doesn’t start in Paris and it doesn’t end in Dakar, having been relocated since 2008 by war and threat of terrorist attack, out of Africa and to South America and other places. What has never changed is the gruelling nature of the race itself. It still tests man and machine more than any race on earth. As Sabine said, it’s “a challenge for those who go, a dream for those who stay behind”.

How the Dakar Works

The rally is divided between transit stages and special stages. For the transit stages, you have to…. well, you transit to the start of the special stage. As such, transit stages are untimed. They are really about getting the riders to the next daunting stretch of wilderness. It’s kind of like skipping out the easy bits of terrain between the really difficult bits.

The special stages are certainly just that. There might be several of them on any single day, broken up by transit stages to get racers past those pesky easy bits of road. There are no points awarded and there’s no benefit in winning a special stage. It’s all about the total elapsed over the course of the entire race. Indeed, there’s one school of thought that suggests one of the worst things you can do is actually win a special stage. Because it means you start the next stage before anyone else, providing other racers with an opportunity to profit from any mistakes you might make.

One thing to be aware of is the complicated and comprehensive penalty system in play. You might get pinged on some small technicality on engine specifications. Or it might be because you made a navigational error. They all add up and add to your overall time.

Then there’s the Marathon Stage. This is when support vehicles and support in general, is removed. There’s no help from anyone and only riders can work on their vehicles. They might help each other (that’s allowed) but there’s no additional parts to be had. So if a slower team member has something you need for your faster vehicles, then they might just have to give it up if you ask them nicely.

Vehicles of the Dakar

Seeing a Quad bike racing past a stricken Porsche is not out of the question in the Dakar. There are 5 categories of vehicles permitted and it makes for some very interesting scenarios.

Motorcycles

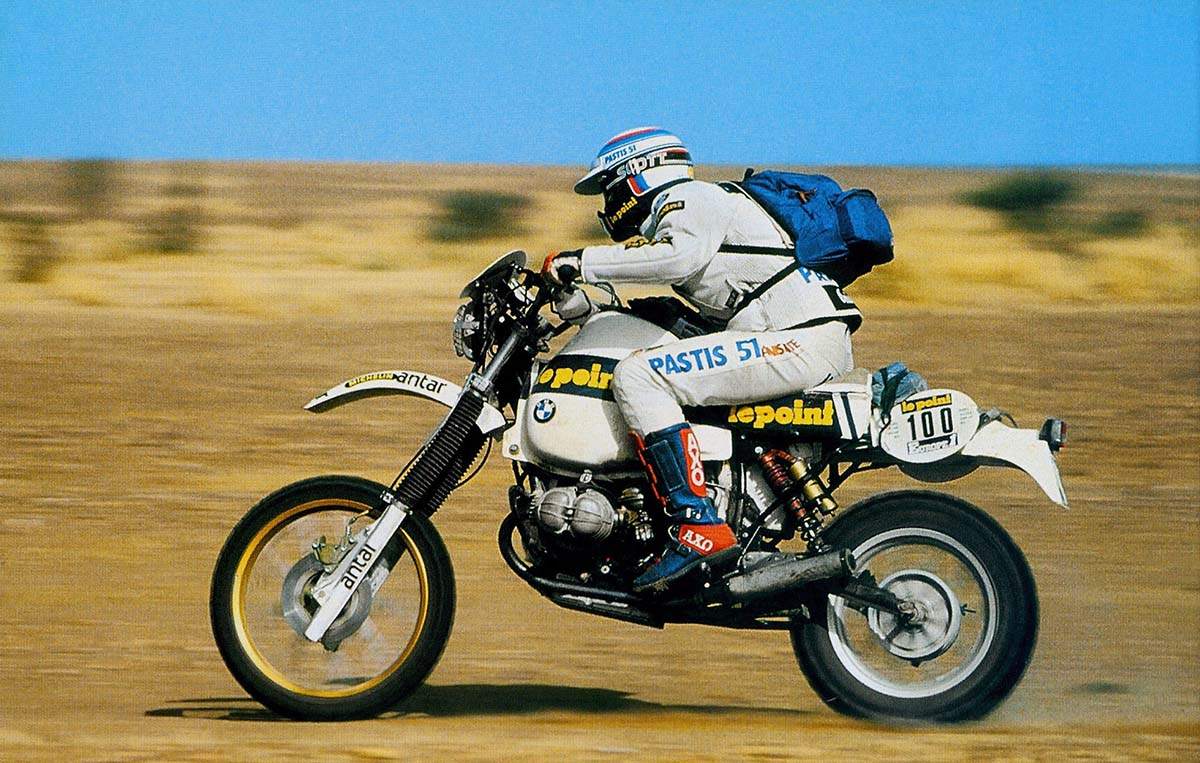

It takes a special type of grit and determination to be a motorcycle rider in the Dakar. Getting stuck in the middle of a desert on your own, with seas of sand sprawling out in every direction, must be very scary. Riders in this category are largely enthusiasts who have shown some riding skill by having previously completed and some qualifying events. All motorcycle engines are limited to 450cc.

Quads

If you decide to compete with a 2-wheel drive quad, then you’ll be strapped into a vehicle with a maximum engine size of 750cc. Opt for 4-wheel drive and you can have an engine up to 900cc.

Lightweight Vehicles

Think Can-Am or Polaris. Lightweight vehicles or SSV's were first introduced to the Rally in 2017. The idea was to provide a more affordable entry class that would allow more competitors to realise their dream of competing. It seems to have worked and now the category is used by factory teams to spot up and coming driving talent.

Cars

There’s a few sub-classes to be found here. First up, you get what’s called the T1 cars. These are very expensive, built from the ground up. These are prototypes that might look like a normal vehicle but they are anything but. Case in point is the monster Hilux raced by Nasser Al-Attiyah.

The next subclass is T2. These are production off-road vehicles which have been modified to suit the race. They are essentially what we can all walk into a dealership and buy, then adapted with the addition of roll cages and larger fuel tanks etc.

The final subclass in an ‘Open Class’. This is where some EVs and those powered by alternative sources race.

Trucks

How would you fancy hurtling over a sand dune in a large truck boasting a colossal 1,150bhp and powered by a 13l turbocharged engine? Well, you can in the Dakar.

The trucks are split into subclasses like the cars and largely follow the same definitions. That is, you either enter a truck based on a production model or build a prototype especially for the race. Where it varies from cars is there is no open class. Instead, you get a rapid response truck class. These are trucks carrying all the spare parts for the cars, motorcycles etc. Yes, in the Dakar even the support vehicles race! Crazy eh.

Legends of the Dakar

As you can imagine for a race so tough, it has pushed to the forefront some remarkable people who feats are legendary.

Hubert Auriol

There from the very beginning, Hubert was the first to win the rally on both two wheels and four wheels. He claimed the motorcycle victory first, in 1981. He’d win again in 1983 before moving to race cars, a category he’d win in 1992.

If claiming victory in two categories wasn’t impressive enough, it’s why he did it that cemented his legend. Towards the penultimate stage of the rally in 1987, Hubert was primed for another victory as fellow Dakar legend Cyril Neveu waited at the finish line. More time passed as the crowd waited. What they didn’t know was Hubert had suffered a terrible accident some 20 kms previously, coming off his motorcycle and hitting a tree. It resulted in him breaking both ankles, including an open fracture to his right ankle. Hubert climbed back on his bike and finished the race. The video of him arriving at the finish line and being helped off his bike is testament to a man of considerable courage and strength.

Vladimir Chagin

Nicknamed the ‘Tsar of the Dakar’, Vladimir has won the truck category 7 times (more than anyone else) and has the second most Dakar stage wins at 63. These days he runs the Red Bull sponsored Kamaz Master team. You imagine everyone listens when he speaks.

Stephane Peterhansel

Mr. Dakar. The Frenchman has won the rally a staggering 14 times, the most recent victory coming in January 2021. Of the record haul, 6 victories have come on motorbike, 8 by car. It’s part of a remarkable 30 year career in the rally raid. To be that good, that consistently, must take not just an almost inhuman amount of talent but a steely determination of immeasurable quantity. If we had a cap, we’d doth it in his direction.

The future of the Dakar

To continue to attract the crowds and international interest, the Dakar is moving with the times. A new alternative energy category is in the works and the rules will be changed to accommodate the technology. This category could make an appearance as early as 2022. Then by 2026, all elite competitors in the car and truck categories will only be allowed to race if their vehicles meet strict ultra low emission standards.

The biggest change is planned for 2030. From that point onwards, both car and truck engines will have to be powered by alternative energy and have zero emissions.

Looking at the history of the rally one thing is for sure, regardless of what powers the vehicles, it’s going to be one tough race. Bring it on.

Dirt track or Dakar, we have tyres for your vehicle.

More tips and articles

Product Spotlight:

Maxxis HT780 RAZR HT

Understand the link between traction and compaction